Hope turned to dread when Brian Flamand opened the door of his Corydon Avenue apartment on the afternoon of Feb. 4.

An hour earlier, Flamand had called the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority’s Mobile Crisis Unit to get some help for his longtime roommate, James Stokes.

Stokes — who is HIV positive and suffers from a heart condition and has a range of mental-health issues — had suffered some sort of crisis earlier in the day. He had become angry, anxious and volatile. At one point, he slammed a baseball bat down on the kitchen counter.

Flamand took the bat away without incident. Afterwards, Stokes went to his bedroom, closed the door and started to watch a movie. That’s when Flamand called the MCU, which provides round-the-clock mental-health services to adults in crisis.

But instead of the paramedics or mental-health professionals Flamand had hoped would come, there were two uniformed Winnipeg Police Service officers standing outside the apartment door.

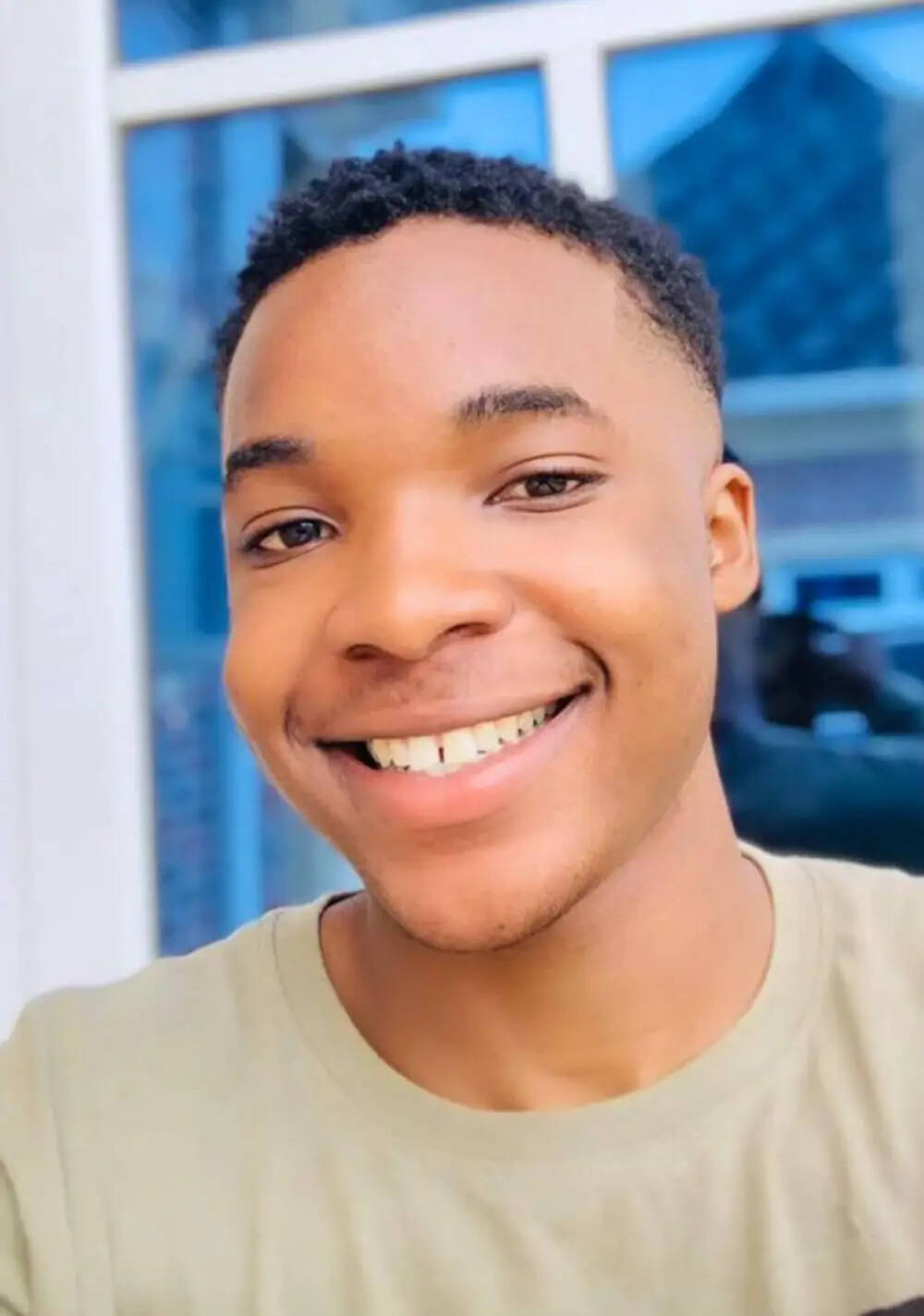

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS FILES

James Stokes (right) says he was left feeling ashamed police had to be called. He and roommate Brian Flamand believe a crisis response team would have handled the situation better.

Unknown to Flamand or Stokes, the MCU immediately triaged the call to 911 asking for police to be dispatched when the incident with the bat was mentioned.

Flamand, who works for an Indigenous health-services agency, said in an interview he specifically did not call police because he was aware that far too often, their mere presence can inadvertently escalate a crisis.

Just over a month earlier, an international student at the University of Manitoba in the throes of a mental-health crisis was shot and killed by police. That incident — just one in a series of police shootings involving mental-health crises — kicked off a new chapter in a long-standing and divisive debate about use-of-force policies that guide police when responding to mental-health calls.

“I knew he didn’t need the police and that a show of force would probably push this in the wrong direction,” Flamand said. Still, he felt he had no choice but to allow police into the apartment.

Flamand said he was quick to inform them Stokes was now unarmed, and was no longer in an agitated state. He offered to approach Stokes and ask him to come out and speak to the officers.

The police declined, directing Flamand to stay in the kitchen while they walked down a hallway and knocked on Stokes’ bedroom door.

Stokes, calm for more than an hour, said he became enraged when he realized the police were inside his apartment.

“The first two officers were soft-spoken but when the other guys show up, they start getting aggressive. The whole situation changed once all the ‘blues’ (uniformed police) showed up.”–Brian Flamand

“I was in my room watching a movie, I had a coffee, I had my door closed. And then I heard all this noise and I remember kind of sticking my head out the door and I’m blinded by flashlights and guns. And I’m like, pardon my expression, but I’m like, ‘F—- no.’ So I closed my door, and I pushed my cedar chest against the door. What would you do if you saw armed people in your home?”

Stokes said he remembered feeling “humiliated” the police had responded, and worried what his neighbours would think about him. He remembered his fear was amplified when he started hearing a loudspeaker from a police cruiser outside his window, which overlooked a parking lot behind the building, demanding he surrender to the officers inside.

As Stokes became more emotional, Flamand said at least six more officers arrived at the suite. They immediately grabbed the dining room table, flipped it on its side, and blocked access to the hallway leading to Stokes’ bedroom. Then, they drew their sidearms.

Flamand said he frantically tried to remind the officers Stokes was not violent, that he did not have the bat anymore.

“The first two officers were soft-spoken but when the other guys show up, they start getting aggressive. The whole situation changed once all the ‘blues’ (uniformed police) showed up.”

“I told them I didn’t want anything from them. I don’t need them here. They’re not welcome. And I said unless they had a bullet for me, they could piss off because I wasn’t hurting anyone.”–James Stokes

Stokes said his composure, hanging by a thread earlier in the day, started to come completely undone. At this point, a situation that started tense was pushed to the point of being out of control.

Stokes admitted he began yelling profanities at the officers in the parking lot behind his building, and in the hallway. He remembered telling them he wouldn’t come out on his own and if they wanted to take him anywhere, they’d have to come and shoot him. He also remembers telling the officers in the hallway that he had a “blood-borne disease” and they should think about that before forcing their way into his room.

“I told them I didn’t want anything from them. I don’t need them here. They’re not welcome. And I said unless they had a bullet for me, they could piss off because I wasn’t hurting anyone. I was in my own room, minding my own business.”

The police interpretation of Stokes’ behaviour was subtly but importantly different.

In the incident report obtained by the Free Press through an access-to-information request, the responding officers wrote that after knocking on his bedroom door, Stokes “immediately escalated and was screaming non-sensically.”

The officers said they were concerned he might be trying to harm himself. They also said Stokes had threatened to bite or spit on officers and infect them with HIV. Finally, they reported Stokes claimed to have a shotgun and threatened to shoot police, an assertion Stokes adamantly denied.

“Brian, you have to understand that you’re a success story because they didn’t kill you.”–Brian Flamand

“It was apparent Stokes was willing to say anything to attempt to get Police to use lethal force,” the lead officer wrote.

Eventually, Stokes came out of his room. Police said in the incident report he had made a sudden move towards another doorway. Stokes denied that, but agreed with the police on what happened next.

Stokes was Tasered twice and lowered slowly to the floor by two officers. He would be transported to the Health Sciences Centre and examined by a psychiatrist, before being released.

Flamand said he has tried to help Stokes process the events of that day. In particular, he wanted his longtime friend and roommate to realize that while he resents the way he was treated, police view the incident in an entirely different light.

“I explained to James many times already, because he circles over this and he ruminates about it, you have to stop, because you have to understand that they believe they’ve done an awesome job,” Flamand said. “Brian, you have to understand that you’re a success story because they didn’t kill you.”

There is a moment of truth every time police are confronted by someone suffering from a mental-health or addictions crisis. It’s the point at which the decisions made in real time will either lead to a peaceful resolution or tragedy.

(Supplied)

Afolabi Stephen Opaso, 19, was having a mental health crisis when Winnipeg police officers were called to an apartment suite at about 2:30 p.m. on New Year’s Eve.

Like on the afternoon of Dec. 31, 2023, when Winnipeg police responded to a 911 call involving a 19-old international student from Nigeria who was in the throes of a mental-health crisis. The call indicated Afolabi Stephen Opaso was carrying a knife and banging his head on an apartment wall. Witnesses said they felt threatened, and thought he might hurt himself.

The moment of truth happened within seconds of police arriving at 77 University Cres. It was 2:30 p.m., and police would later say they found Opaso in a frantic state wielding two knives.

In an audio recording released by lawyers representing the family, police can be heard to yell “drop the knife” three times. The recording was 26-seconds long, but it took only nine seconds from the first command by police until the first shots were fired.

Could police have made a different decision when they reached that moment of truth? Policies on the use of lethal force are crystal clear, that when someone is armed and poses a potential for “grievous bodily harm” against an officer or others, the use of lethal force is warranted.

Opaso’s family isn’t so sure.

Opaso was, by all accounts, frantic and carrying knives. Still, his family continues to wonder if an alternative approach, perhaps one not involving police, would have produced a different outcome. “You don’t have to shoot a boy going through a mental-health crisis,” Opaso’s sister, Yemisi Opaso, told the Free Press. “There are better ways to respond to mental-health crises.”

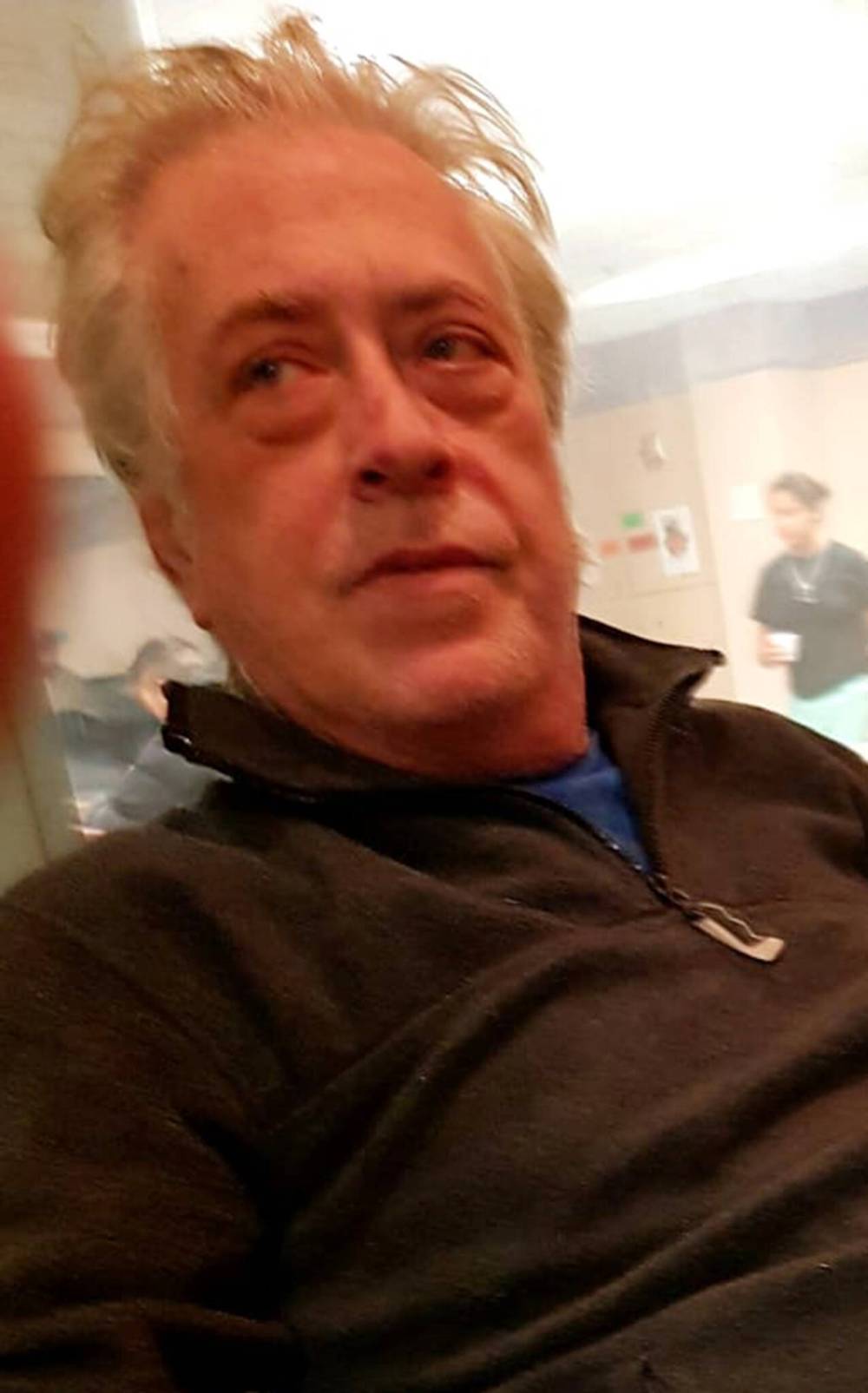

SUPPLIED

Bradley Singer died after police tried to apprehend him under a Mental Health Act order.

The same moment of truth was present on Feb. 13 — when Winnipeg police shot and killed 59-year-old Bradley Singer, who suffered from schizophrenia. It was the second time in two months police had been directed to execute an order under the Mental Health Act and apprehend Singer for failing to meet with his psychiatrist or take his medication, and submit to a non-voluntary medical examination.

When police arrived at Singer’s Magnus Avenue house, he refused to come out. A police negotiator tried to get him to surrender. Instead, he sprayed a fire extinguisher at the officers. The situation was then handed over to the WPS tactical support team, which used a battering ram on an armoured vehicle to break down the front door.

Police later said Singer, who lived alone, was armed with an “edged” weapon. He was shot several times; he died a short time later in hospital.

Singer’s older brother Gerry said he has not been able to obtain any additional details about the confrontation that were not released by police immediately following the shooting. However, when he visited the house days later, he counted 17 bullet holes in the walls near where his brother was shot.

Gerry Singer said despite the fact police twice sent the tactical unit to apprehend him under a Mental Health Act order, he had no pre-existing record of violence and there was no evidence he was acting erratically.

“Brad was sick, but he was one of the most peaceful people you could ever meet,” Gerry Singer said in an interview. “He wasn’t a violent person at all. I don’t know why they had to go in and get him. They could have just let him stay there, or asked me to come talk to him. I don’t understand why this happened.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

Gerry Singer says his brother Bradley was non-violent. He says police should have waited out the situation to allow it to defuse.

Was a full police intervention involving lethal force the only option in both of these tragic incidents? It’s a difficult question for all sides to answer.

Investigations by the Internal Investigations Unit of Manitoba (IIU), a provincial body that examines all police-involved shootings, and coroner’s inquests tend to focus on whether police were justified in applying lethal force after someone had become violent. Rarely are there opportunities to determine if the presence of police helped escalate the situation to the point where a life needed to be taken.

Even mental-health advocates and professionals acknowledge that if someone is already violent, armed or is threatening the safety of others, law enforcement is likely the most appropriate response.

Community-based response teams making a difference

What if it never becomes a crisis?

As communities across the country suffer under the strain of a tsunami of mental-health and addictions crises, advocates and health-care professionals are asking governments to consider addressing the problems “upstream” and before police or paramedics need to be called.

What if it never becomes a crisis?

As communities across the country suffer under the strain of a tsunami of mental-health and addictions crises, advocates and health-care professionals are asking governments to consider addressing the problems “upstream” and before police or paramedics need to be called.

Although many cities, including Winnipeg, are experimenting with co-response programs — where a mental-health worker is partnered with a police officer — an increasing number of communities are deploying teams built around mental-health professionals and people who have themselves struggled with mental health and addictions.

In British Columbia, the Peer Assisted Care Team (PACT) program — a partnership between the provincial government and the B.C. branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association — pairs professionals, such as clinical counsellors, social workers and nurses, with a trained civilian peer, typically someone who has related lived experiences.

Kim McKenzie, director of policy with the Canadian Mental Health Association, BC Division, said that when PACT was launched on a pilot basis in 2021, it initially served North West Vancouver, New Westminster and Victoria. This year, it was expanded to include Prince George, Kamloops and the Comox Valley and there are expansion plans to identify at least four additional communities — including dedicated teams for Indigenous clients.

McKenzie said PACT starts with dedicated phone and text lines that allow people to connect with a mental-health professional in their community without having to go through 911. Depending on the risk level and acuity of the crisis, those calls are triaged to determine the best possible response.

In some instances, paramedics may be needed and in others, a police response may be most appropriate. As well, PACT teams do not execute orders under the provincial mental health act.

However, the overall philosophy of PACT is to avoid using police or other uniformed emergency services to prevent someone in the early stages of a crisis from escalating.

“These teams don’t come in with sirens and weapons and uniforms,” McKenzie said. ” It’s very relaxed, very person-centred. And the person has to consent to being served by PACT.”

Once that is provided, McKenzie said, the individual not only receives help on an emergent basis, but is also provided with a wellness check within 48 hours of the first call to PACT, and help with referrals to mental-health professionals for ongoing care.

“For the most part, these teams are actually diverting calls to 911, and diverting a number of calls away from emergency rooms,” McKenzie said. “Because they’re able to support people where they’re at, spend the time with them to co-regulate and de-escalate. So we’re actually allowing people to come through their crisis, whether it’s at their homes and (in their) community, and then really ensure that they’re connected to the support systems and the health-care system to get things that they need to get well.”

Although incidents involving someone who is violent or armed with a weapon are still triaged to police, PACT has been able to effectively respond to calls involving potential suicides.

“The most common call we get is around suicidal ideation and self-harm. We’re not just responding to people who are talking to themselves on the street. We are responding to very high-acuity suicidal calls. Our data tells us that these teams are changing and saving lives.”

– Dan Lett

However, there are still questions about how police intervene in the most volatile incidents and whether there are other, less-volatile situations where police may not be involved or only be present to support the work of mental-health professionals. However, as it stands now, when there is any hint of violence or volatility, police are the first and only response.

There are two primary ways police become involved in mental-health or addictions crises: reports of violent or volatile behaviour that go directly to 911; and through orders issued under the Mental Health Act to apprehend someone for involuntary treatment or examination.

Could other non-police entities be used in some or all of these instances? Legally, it’s precarious.

Manitoba’s Mental Health Act currently stipulates “peace officers” are the only ones authorized to execute orders to bring someone in for an involuntary examination or treatment. Applications for these orders usually come from physicians who are treating the individual in question, or concerned family members.

Manitoba is not unique in this regard: a Free Press audit revealed that every province singles out police or peace officers as the only entity authorized to affect orders issued under mental-health legislation. This requirement is in place even in situations where the subject of an order has not demonstrated any violent or threatening behaviour.

However, as tragic shootings continue to occur, there is increasing pressure on provincial governments to allow for a broader range of responses, even in some situations where a legal order under the Mental Health Act needs to be executed. (Housing, Addictions and Homelessness Minister Bernadette Smith recently told the Free Press her department is undertaking a review of the act to see if it needs to be updated to allow for a broader range of responses to orders.)

In most provinces experimenting with alternative responses, there are two main approaches: the creation of co-response programs — teams involving police and mental-health professionals — and 100-per-cent civilian programs.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

Provincial minister Bernadette Smith says her department is undertaking a review of legislation to consider allowing for a broader range of responses to Mental Health Act orders.

In Winnipeg, the WPS and Shared Health’s Crisis Response Centre collaborated to create ARCC, the Alternative Response to Citizens in Crisis. A pilot project first launched in 2022, ARCC sees teams involving both a plain-clothes officer and a mental-health clinician dispatched to mental-health or addictions calls that do not require a police presence.

As part of this program, a mental-health clinician is available seven days a week, 12 hours a day to triage incoming calls to ARCC, and to provide real-time health information to responding officers. This information can include recent contacts with the health-care system for mental-health concerns, and the number of times the individual may have contacted 911.

In its first year, ARCC teams responded to 882 incidents involving 530 different individuals. More than 80 per cent were resolved without any involvement from police. That meant officers spent considerably less time escorting people to hospital and then waiting with them until they could be seen by a mental-health professional.

More importantly, more than 90 per cent of the people that came into contact with ARCC teams were able to remain in the community rather than being admitted to a health-care facility. Part of this is due to ARCC’s mission to create community-support plans and to perform regular wellness checks on the people they come into contact with.

Based on those results, the program was made permanent in 2023 with plans to move to a seven-day-a-week model. Unfortunately, a shortage of mental-health professionals has slowed its expansion.

That shortage means police are still responding to thousands of calls involving mental-health or addictions crises, and executing orders under the Mental Health Act.

Winnipeg police said that in 2022, they were asked to perform an average of more than 21,000 wellness checks annually, many of which involve people with mental-health challenges. That is 15 per cent higher than the five-year average, and works out to about 58 per day.

Of those calls, roughly 2,000 were related to orders issued under the Mental Health Act, which most-often involve having to apprehend someone for involuntary examination, hospitalization or treatment. Police have also said, without offering specific data, that the “vast majority” of these calls do not involve violence.

Mike Deal / Free Press files

Insp. Helen Peters says officers routinely go through extensive training on de-escalation with a focus on eliminating the need for lethal force.

The data shows there is room for ARCC to grow if the right resources can be found. Recognizing expansion of ARCC will take time, the WPS has made significant efforts to train its officers on de-escalation strategies and educate them on the complexities of mental-health and addictions crises.

Insp. Helen Peters, the WPS mental-health liaison and lead officer for ARCC, said in an interview Winnipeg officers go through exhaustive annual training in de-escalation techniques and how best to respond to these types of calls.

Each year, officers do a two-day training course, with one day devoted to de-escalation and one day for mental-health education. These scenario-based training sessions are then augmented by online courses. The training borrows from programs developed by other law enforcement agencies, as well as ongoing consultation with representatives of the health-care system and community mental health agencies.

Peters said the training is focused on eliminating the need for lethal force.

“I think the better way to describe it is that we’re trying to give all our officers all the information possible to stop (an incident) from ever getting to that point,” Peters said. “So we’re talking about behaviours, we’re talking about triggers, we’re talking about language, we’re talking about (how) what you wear matters. We’re talking about (how) distance matters. But more than that… once you’re in a use-of-force moment, what you have to do is employ of all of (the training) to prevent that from happening.”

“I think the better way to describe it is that we’re trying to give all our officers all the information possible to stop (an incident) from ever getting to that point.”–Insp. Helen Peters, the WPS mental-health liaison and lead officer for ARCC

Peters said if someone is armed and violent, protocols on the use of non-lethal and lethal force must — for the safety of police and bystanders — take precedence. Thus, while the WPS supports the increased involvement of hybrid response teams and an increased role for civilian responses, they are not appropriate in all situations.

“We need to look at it in (the sense) that there is no one fix, there’s no one tool that’s going to be able to do what needs to be done to find the best path forward in order to ensure that all of these people … get the best help that we can get them.”

That is largely the approach being taken by health-care professionals, who have collaborated with the WPS on the creation of ARCC and its protocols for response.

Dr. Jitender Sareen, the province’s medical specialty lead for mental health and addiction, said health-care professionals and police are both focused on finding a better way to relate to people in crisis.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS files

Response teams involving both clinicians and police have proven successful, Dr. Jitender Sareen says.

It is well accepted by everyone involved that a police response to a mental-health crisis can produce “unintended consequences” that trigger more violence and volatility, Sareen said. The key is finding the resources and the program structure to provide every crisis with the best possible response.

“We know that when somebody in crisis sees police officers, they get triggered, and they get stressed,” Sareen said. “So how do we ensure that a clinician and police can respond together in as many appropriate forms as possible? That is the direction that I think would be the right way for our city to go. And that’s where I think a lot of other jurisdictions are also going.”

Sareen noted that in its first year, ARCC was tasked to respond to Form 14 orders under the Mental Health Act, which involves someone who has absconded from hospital but needs to be returned for further treatment.

In the past, Sareen said, police would have been the only option. However, a risk assessment suggested they could be handled differently. On a pilot basis, ARCC teams were able to enforce some Form 14 orders without incident. This suggests it might not be necessary to perform a long and protracted review of mental-health legislation.

“I think our vision would be that (ARCC could be used) for other forms, potentially, if if there was appropriate supports and appropriate funding without even having to change the act,” Sareen said.

Although advocates have applauded these first cautious steps toward reducing police involvement in mental-health and addictions crisis intervention, there is an overwhelming sense more needs to be done to remove police from many of these calls, and it needs to be done quickly.

“How do we ensure that a clinician and police can respond together in as many appropriate forms as possible? That is the direction that I think would be the right way for our city to go.”–Dr. Jitender Sareen

“We have publicly stated our concerns around police involvement around the increased role that police play in wellness checks, the criminal-based approaches to dealing with mental illness and the absence of investment in community-based support,” said Sarah Kennell, national director of public policy for the Canadian Mental Health Association.

In many ways, Kennell said, police have been unfairly burdened with the responsibility of responding to mental-health crises, an unintended consequence that began during the de-institutionalization movement following the Second World War. At that time, there was a consensus warehousing people with mental-health issues in secure institutions was inhumane and ineffective.

As a result, thousands of patients were released, with robust pledges to increase support for community-based treatment and support, she said. Unfortunately, those investments never came to fruition and the former patients of mental-health institutions were left largely to their own devices.

Without community supports and “upstream interventions” that help people avoid falling into crisis, the entire burden fell on police, she said.

Unfortunately, Kennell said the lingering stigma and fear around mental illness fuels the public’s willingness to accept police as the principal method of intervention. That does not mean Canada cannot look for new approaches, she said.

“In a country like Canada, no one should have to die because they have a mental illness. I think that’s the endpoint we need to be keeping in mind.”–Sarah Kennell

Provincial branches of the CMHA are involved in several pilot projects that involve police and mental-health professional teams like ARCC, or fully civilian responses, Kennell said. This is part of a national effort to explore every opportunity to take calls away from police and direct them to mental-health professionals.

Decades of research show conclusively that when police are the principal responders to a crisis, the outcomes are overwhelmingly bad, Kennell said. On the other side of the equation, she added, jurisdictions that have invested in co-response or community-based programs have seen dramatic decreases in the number of police shootings.

“I think it would be inaccurate to say that solely a community-based response to dealing with mental-health crises would be the solution,” Kennell said. “But in a country like Canada, no one should have to die because they have a mental illness. I think that’s the endpoint we need to be keeping in mind. It’s just unacceptable to me. These stories are happening all the time, every day. Every day.”

Could a different approach have been used by police when responding to the incident involving James Stokes?

The WPS had initially promised to answer more questions about the specifics of their response once confidentiality waivers were obtained by the Free Press from Stokes and his roommate Brian Flamand.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS files

Brian Flamand (left) and longtime friend James Stokes argue the presence of police often escalates an already potentially volatile situation when an individual is experiencing a mental-health crisis.

However, even after those waivers were obtained, police declined to make any further comment.

“It appears the complainants in the matter … may dispute some aspects of the police report,” a WPS spokesperson said. “We cannot speak to the decisions that were made at a given call from our vantage point. A formal complaint process is available to citizens via LERA (Law Enforcement Review Agency) and PSU (Professional Standards Unit) if they are dissatisfied with police conduct.”

As for Stokes, he is still struggling daily to process the events from February.

Stokes said he is ashamed police even had to be called. But he is also angry, and not just about the way police handled the situation.

After being taken to hospital, he was admitted for several days for observation. Upon his release, Stokes said he was told he was going to be referred to a psychiatrist to follow up on the mental-health problems that contributed to this incident.

He’s still waiting.

“It’s six months later and nothing.”

Dan Lett

Columnist

Dan Lett is a columnist for the Free Press, providing opinion and commentary on politics in Winnipeg and beyond. Born and raised in Toronto, Dan joined the Free Press in 1986. Read more about Dan.

Dan’s columns are built on facts and reactions, but offer his personal views through arguments and analysis. The Free Press’ editing team reviews Dan’s columns before they are posted online or published in print — part of the our tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.